My Final Battle with WPW: Recovering from Heart Surgery

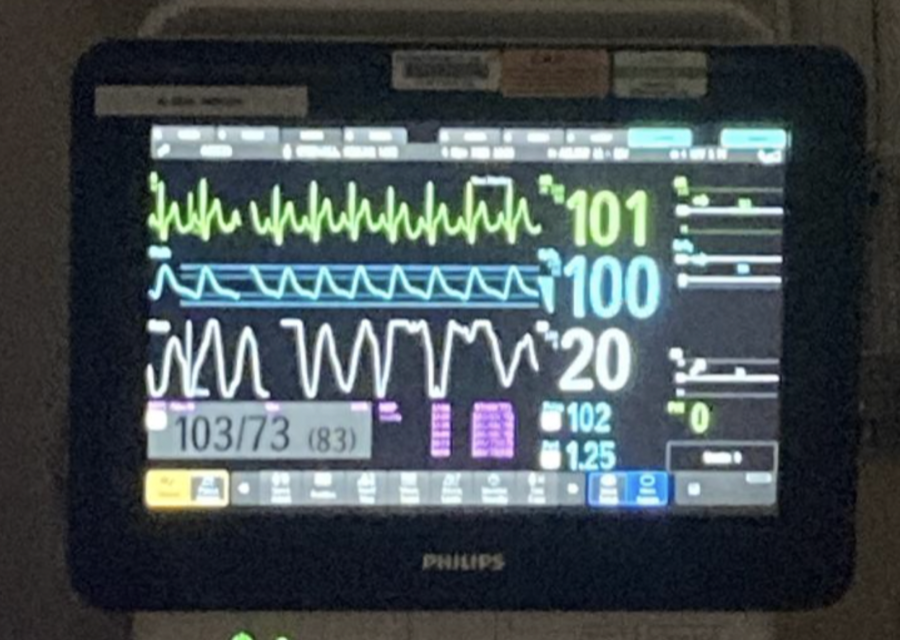

Machines monitor Aster’s vitals after the surgery.

The surgery is called catheter ablation. It is composed of three parts, each supposed to take only 1 to 2 hours. First, the doctors do some mapping; poking, and prodding, ultrasounds of the heart called echocardiograms are part of the mapping doctors do, as well as running other tests as necessary. Once they’ve found the issue, it is time to do the ablation. Doctors use catheters from different angles in order to reach their destination. In my case, they were using catheters in my groin and neck in order to reach my heart.

When they reached their destination, their goal was to freeze the extra channel. Then, if successful, they spent the next two hours doing trials and testing, which are the tensest. Doctors adjust the heart rate in different ways to make sure that the heart can go back to a normal beat on its own.

My surgery was scheduled for November 4th. I had a million reminders set on my phone, and the date was circled in neon red marker on all my calendars. For the entire week preceding it, I was filled with that mixture of excitement and nervousness. It was a feeling no one has a name for. I was excited; not so much for the procedure, but for getting over recovery and being able to drink caffeine and do cardio without worries. I was also nervous because I knew what could go wrong. I’d read a million articles, and I knew all the risks.

When I got there, each nurse and doctor came in to greet me. My nurse, Betsy Giver came in to draw blood, and I was immediately comforted by her warm smile. Finally, the man I had been waiting for, my cardiologist, Dr. David Spar, walked in with a lopsided grin on his face. “You’ve got it this time, right?” I asked. He nodded and gave me a fist bump. Before I knew it, the wheels beneath me were rolling and I was on my way to the surgery room.

Waking up, I was immediately ready to sit up, eat something, and then leave. Spoiler alert: they did not let me do that.

After bringing my family in, Dr. Daji Takajo came in to reveal that the surgery was a success. He explained that I had been under for 8 hours and that there was only a 10% chance of recurrence, but I was too excited to listen to him. I couldn’t stop thinking about all of the things I didn’t have to worry about anymore. My eyes were opened to a world of caffeinated drinks and high-cardio activities, and I was stoked.

He snapped me out of my daydream. However, he broke the news to me that I had to sit in the hospital bed, perfectly still, not moving my legs or neck, for four hours before I could leave. My immediate thought to this news was, “What I wouldn’t give to punch this guy,” but of course, that would require me to move my legs and neck.

After the longest four hours of my life, I was finally able to go home. Of course, there had to be a million more rules, but I didn’t mind. My mother was originally dead set on the fact that I would not be allowed to go back to school on Monday. However, I was already going stir-crazy, so I didn’t give up. Eventually, my mom got tired of my begging and let me go back to school that Monday.

My recovery was smooth sailing until I tried to go up the stairs to my bedroom. After going up the stairs I immediately felt nauseous and ran to the bathroom. I then proceeded to vomit half of my body weight into my freshly-cleaned bathtub. This whole vomit fiasco definitely didn’t support my case that I would be able to return on Monday, but to my surprise, she let me go anyway.

That day at school was amazing. Everyone was super mindful, and some of my classmates surprised me with cards or small gifts, and the nurses didn’t think twice about giving me an elevator pass. Everyone was shocked to see me back so soon, and I had never felt so loved and supported in my life. The entire experience really opened my eyes to how much the people I love care about me.

From then on, everything went smoothly. My surgical sights healed perfectly and at my two-week checkup, Dr. Spar was happy to announce that everything looked good. However, his overuse of the words “currently” and “for now” left a feeling of uneasiness in my stomach.

Today, I am grateful for my experience with WPW. I am currently gathering a team to walk in the “heart mini marathon” for Cincinnati, and I have been able to spread information about heart-related issues. My WPW has helped me grow as a person, and thanks to it, I am more open-minded and ambitious. It taught me not to give up when things go poorly, and to speak up when things feel wrong. I don’t think I’d be where I am today without this experience, and I am grateful for that.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Highlands High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.