Kentucky House Bill 149 presents fiscal dilemma surrounding public education

HB 149 establishes a tax credit voucher for families who send their children to private schools.

Kentucky’s decades-long struggle for public education funding has accelerated in recent years. Now, the Commonwealth and the country at large face fiscal dilemmas that are sure to shape the future of public education for centuries.

The two largest state pension programs in Kentucky, the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) and the Kentucky Retirement Systems (KRS), tanked in 2018 following patterns of underfunding, faulty investment, and a collapsing stock market. These pension concerns led to widespread teacher protests, mimicking those that were occurring elsewhere in the United States at the time. Former Governor Matt Bevin’s attempts to address the problem resulted in significant losses for public sectors, including education.

According to the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, school “formula” funding in Kentucky (SEEK program) was providing 13% less per student in 2019 than in 2008 (adjusting for inflation). These cuts rank fourth worst in the nation. In the 2018-2019 fiscal year, Kentucky saw a decrease in formula funding (adjusted for inflation), the only one out of five states that experienced significant teacher protests.

Many of the policies that have allowed these funding cuts to continue were endorsed by former Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and her administration. Although she no longer holds the position, her legacy of increasing support for charter and private schools at the cost of public education continues to resonate with Republican legislatures across the country. Kentucky is no exception.

Recently, this sentiment has been best exemplified through the increasing popularity of voucher programs in state legislatures. Each voucher bill has slight differences in verbiage, but all of them function in similar ways.

Voucher programs extend tax credits to families who send their children to private schools. In theory, this tax break intends to help families pay for private school by exempting them from paying the portion of their taxes that usually funds their local public schools. However, the income threshold to qualify for these tax breaks is often high. Critics argue that this high threshold excludes low-income families from benefiting.

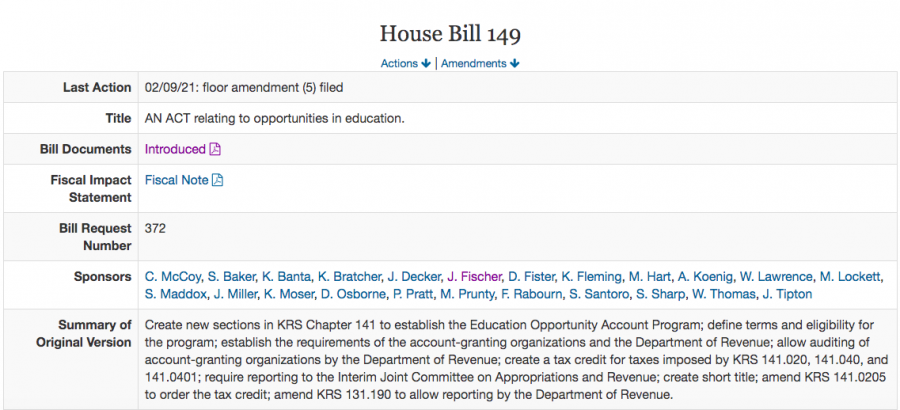

In Kentucky, there is a similar piece of legislation circulating in the House of Representatives. The bill is called House Bill (HB) 149, and it outlines a plan for the creation of the “Education Opportunity Account Program,” which touts the same tax credits seen in most voucher bills. It has explicitly been stated that HB 149 is not a voucher, but it undeniably mimics voucher programs from other states. The qualifying income for the EOA program as detailed in HB 149 is approximately $121,000, reinforcing concerns regarding high income thresholds. The bill, if implemented, is set to divert approximately $8.6 billion away from public schools by 2040.

Current Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear campaigned with the promise of increased funding for public education, but there have been obstacles in achieving that promise. HB 149 is the most recent manifestation of these obstacles.

The Education Opportunity Account Program as detailed in HB 149 is modeled after a similar system in Florida. Florida has multiple voucher programs in place, and there is currently a Senate bill being proposed that would expand the use of public funds and decrease audits from every year to once every three years.

Dr. Karen Cheser, Superintendent of Fort Thomas Independent Schools (FTIS), is strongly opposed to HB 149 for a variety of reasons. Primarily, she is concerned about the bill’s fiscal impact on FTIS and the Commonwealth as a whole. Cheser explained that there is one pot of money, SEEK funding, that is allocated for all public schools in Kentucky and divided up between districts. With tax credits enacted for students who choose private school instead, the overall pot is set to shrink significantly.

“We as a school district, just like every other school district, would be provided funding from [SEEK], but that funding would be less because there would be less in the pot. That would be overall bad for Fort Thomas Independent Schools, but we’re also intertwined and interrelated with all of the different school districts and all of our students. It would impact the entire state in a very negative way.”

Further, a decrease in state funding requires public school districts to increase revenue from local taxpayers. This leaves little ability to fund extra amenities for engagement, such as extracurricular activities, field trips, professional development, and technology.

According to the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, state funding nationally declined by $166 per student between 2008 and 2016, while local funding has grown by $161 per student. In Fort Thomas specifically, FTIS now receives approximately 10% less state funding than it did in 2008. On a broader scale, this means that more districts rely on local taxes to fund public schools, and less districts can accommodate the costs associated with extra amenities for students and staff.

This gap exacerbates pre-existing inequities within communities, as low-income areas remain low-income and the quality of the schools do not increase, while higher-income families can afford to send their children elsewhere.

Proponents of HB 149, and similar voucher programs across the country, argue that the tax credit gives families more choice in their childrens’ education. However, considering the income discrepancies apparent throughout the legislation, Cheser believes the aspect of choice is not a reality for all students.

“Typically, it’s the people who are already spending money on private school tuition that are the ones benefiting. Not the lower socioeconomic students. Not students who have disabilities. Not students [from] underrepresented populations. Many times they don’t have access to these schools.”

There is no language in HB 149, or similar bills, protecting marginalized populations from discrimination based on factors such as disability status, religion, or having English as a first language. Some outstanding amendments proposed to the bill attempt to rectify these, including an amendment to allow homeless youth to participate and provide resources and accessibility for English language learners. However, these have not yet been approved by a vote.

Voucher programs were first introduced following the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), which desegregated public schools across the country. They allowed white parents to send their children to segregated private schools using public funds. Educators and administrators alike fear this history of inequity continues to permeate this type of bill.

Aside from the inequity presented by HB 149 and similar bills, there exists another concern for stakeholders: constitutionality.

In Section 189 of the Kentucky state Constitution, it specifies, “No portion of any fund or tax now existing, or that may hereafter be raised or levied for educational purposes, shall be appropriated to, or used by, or in aid of, any church, sectarian or denominational school.” This essentially means that public funds are barred from use for private schools.

HB 149 has 23 co-sponsors, including Rep. Joseph Fischer (R), who represents Kentucky’s 68th district. Fischer is a Fort Thomas native and an outspoken conservative. Fischer did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the bill or its progress.

The twin bill of HB 149, Senate Bill 25, has not gone as far in the Kentucky state Senate as HB 149 has in the House of Representatives. It is still in committee and has not been scheduled for a vote. Senator Wil Schroder (R), representing District 24, responded to a request for comment. Via email, he noted that he does not sit upon the committee which is reviewing the bill, and mentioned that he is “still doing research on it.”

The weight of HB 149 invigorates educators in their advocacy for increased public education funding. Cheser believes now more than ever, it is important that public schools are financially supported by the Kentucky legislature. If there is long-term investment in public education, Cheser points out, the need for funding in other sectors, such as prison and healthcare, will shrink.

She said, “If you look short term, you might think, well we just don’t have money for education. But we’re hoping that our legislators look long term. In order to reduce that prison population, in order for people to be well, and to have better healthy habits, we feel that investing in education will impact those positively.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Highlands High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

Scott Johnson • Feb 23, 2021 at 6:34 am

Kentucky State Representative Joe Fischer, like Mitch McConnell, does not work for his constituents, but they keep re-electing him anyhow.

The General Assembly has a history of only responding to litigation.

When Jack Moreland was Superintendent of Dayton Independent, he and the Council for Better Education sued the General Assembly in the late 1980s, won, and that led to the Kentucky Education Reform Act, (KERA, 1990) and the current Support Education Excellence in Kentucky, (SEEK) funding formula.

Although composite Constitutional and caselaw language directs that the General Assembly shall “adequately, equitably, and primarily fund the state system of common schools, and shall not shift that funding burden onto localities”, the General Assembly has consistently violated every element of this legal mandate.

Why?

1) The rural majority holds a majority of votes in the General Assembly, but as most of this is comprised of agricultural property which is exempt from the local property taxes which comprise the local portion of school funding in the majority of districts, it is considered equitable for them to take more than their share of state funding, because they are “poor”, (poor in tax revenue, Federal funding addresses actual poverty, which Kentucky funding is precluded from doing) while deliberately short-changing 10% of districts, primarily clustered in the Triangle of Greater Louisville, Greater Lexington, and Northern Kentucky.

With the Teapublican majority in the General Assembly being chronically weak on raising adequate revenue, this body carried the illegal shifting of the burden onto locals in order to compensate for its negligence, a step further by passing KRS 160.470, aka HB 44 just over 40 years ago.

This legislation enables cities, counties, and school boards to increase local tax revenue by 4% per year without voter recall. The reality is that they are not just enabled, but forced, given the absence of credible funding from Frankfort, to impose these perpetually-increasing local taxes, or else face a perpetual reduction in the services which they provide their constituents.

Given that the General Assembly IS NOT increasing funding, local districts like Fort Thomas must increase local taxes by 4% per year, compounded, in order to survive.

Could legal action force legislative relief again?

Fort Thomas, Boone County, and Beechwood filed an Amicus Brief in Young V Williams, (2007) adding a link between equity and the adequacy argument being made by the Council for Better Education in this case.

While Franklin Circuit Judge Thomas Wingate rejected the CBE’s adequacy argument, he explicitly expressed favor for NKY’s equity argument as being actionable, declaring that should NKY file litigation based on equity, he envisioned such action providing a vehicle for his declaring the discriminatory SEEK formula un-Constitutional.

Despite my efforts in Chairing the Funding Task Force and cultivating interest among adversely impacted districts during my FTIS Board Service, (2007-2014) my fellow Board Members, as well as the Fort Thomas Education Foundation, were dismissive toward the notion of accepting Judge Wingate’s invitation to litigate.

While a pro bono legal team successfully secured the reinstatement of the Highlands Football schedule, which the team had been forced to forfeit due to residency findings by the KHSAA in connection with the disputed residency states of player Mike Mitchell, (later NFL’s Mike Mitchell) securing funding relief for Fort Thomas taxpayers, even with an open invitation from the court of jurisdiction, was not deemed worth the time or effort.

It seems that by making residence in Fort Thomas a literally more disproportionately taxing proposition, the Board and Foundation resolved that paying high local taxes was an elitist price of admission to Fort Thomas.

After my departure from the Board in 2015, the Funding Task Force was disbanded. Fixing state funding was no longer on the FTIS radar screen.

While it is good to hear the outgoing Superintendent Dr. Karen Cheser articulate the gravity of this untenable situation, the Fort Thomas voter propensity for keeping Representative Joe Fischer, working here against FTIS, (again) means that the anticipated outcome will be for the onus to perpetually increase local taxes in order to support FTIS, will continue to increase the price of admission to the Fort Thomas community as a means by which to benefit from a Fort Thomas Education.

Scott Johnson

FTIS Board of Education Member

Chairman, Funding Task Force

(2007-2014)

Mrs. Dawn Hils • Feb 22, 2021 at 11:03 pm

Excellent reporting! Very well researched and explained. Timely and important!

Larry Smith • Feb 22, 2021 at 10:57 pm

As an aging boomer, I am ashamed of my generation. Our parents made sacrifices (paid higher taxes) so that my generation could get a good education. My generation and those immediately following have not reciprocated their ancestors sacrifices. As a result, despite many excellent schools, teachers, and students, our total educational system is falling behind many others. We are creating a national tragedy, unless we halt slide now.

Larry Smith

Interim Pastor

First Christian Church

Fort Thomas